"It seems to me that to organize on the basis of feeding people or righting social injustice and all that is very valuable. But to rally people around the idea of modernism, modernity, or something is simply silly. I mean, I don't know what kind of a cause that is, to be up to date. I think it ultimately leads to fashion and snobbery and I'm against it." Jack Levine: January 3, 1915 – November 8, 2010 LEVEL BILLIONAIRES OUT OF EXISTENCE

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Human Revolutions Have A Record of Failing To Reach The Aspirations of The Magnificat

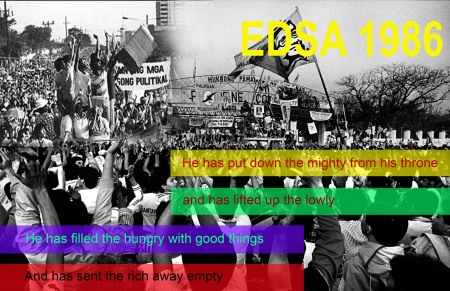

Commentaries on EDSA [The People Power Revolution in the Philippines]1986 never fail to point out the significant role of religious imagery.

Two of the most prominent are the Sto. Nino and the Blessed Virgin Mary. In fact, the church-sponsored monument to EDSA is a statue of the Virgin Mary festooned with birds. The birds presumably symbolise freedom, from the lines of Bayan Ko – “Ibon mang may layang lumipad.” Soon after, this did not escape the irreverent humor of Pinoys who called the statue “ang babaeng mahilig sa ibon.”

At some point of the EDSA triduum, even Fidel Ramos held high a statue of the Virgin Mary. When I saw this, I thought to myself, since he is a Protestant: “Was his gesture ecumenical, or political?”

The Virgin Mary continues to occupy a special place in popular religious imagination. Some cultural commentators say it reflects the mother-centric Filipino family. I don’t know when it started, but the affectionate title of “Mama Mary” has gained currency, though it doesn’t quite resonate with me.

The Mary that I relate to with greater fervor is the Mary of the Magnificat.

Particularly these four lines of her song, which welled up from within my subconscious, when I was looking for a way to explain what happened and did not quite happen after EDSA 1986.

He has put down the mighty from his throne. This happened and we have reason to celebrate.

And has lifted up the lowly. Not quite. But EDSA opened up possibilities for this, with the acknowledgment that “people power” is the basis for the new government’s legitimacy.

In more secular language, I had hoped for the institutionalisation of a more participatory popular democracy. But as the political situation “normalised” it appeared that what was being institutionalised was “elite democracy.” In the language of the Magnificat, in place of the one mighty removed from power, what we got were many factions of the mighty competing for power.

Should we dismiss, then, with disappointment, such limited gains of EDSA? I prefer to see the possibilities in the “democratic space” of an elite democracy compared to an elite dictatorship. But to seize the opportunities of “lifting up the lowly” we would have to recalibrate the forms of struggle and organisation of people power, from the dominant tradition of resistance, to an exploration of critical participation and engagement.

He has filled the hungry with good things. I remember an editorial cartoon of Boogie Ruiz that showed smiling people flashing the Laban sign from the open windows of their cars, as yellow confetti rained down on them. At the sidewalks, a group of kariton pushers ask themselves: “Does this mean that we will now stop being poor?”

This reminds me of a slogan attributed to the poor people’s march in Thailand – “We want a democracy that we can eat!”

The answer to the question is partly linked to the fourth line: And has sent the rich away empty.

For sure, some of the very rich were sent away, but not empty. They took quite a bit with them, in addition to what they had already sent ahead to their destination. But most of the others stayed behind, switched sides, and held on to what they had.

For the hungry to be filled with good things post EDSA, justice is essential, in the form of retribution and redistribution.

Post-EDSA reality is complex, and the strategies needed to fulfil the promise of EDSA are not as simple and unambiguous as these four lines from Mary’s Magnificat.

But I wish someone would do a painting or a sculpture of Mary that captures the fervor of those four lines of her, and our, hope.

The fact that we constantly fall short of the aspirations set out in The Law and the prophets, including those in The Gospel is an expression of the fact that we are human whereas those aspirations aren't the product of merely human imagination. Without a belief in the obligation to try to make them real in real life, the inertia of disbelief takes over, corners are cut, exceptions made - generally by those in a position to cut themselves exceptions - and, eventually or rapidly, the revolution is as bad or worse than what it overthrew. But that will get me on the daft reverence that the anti-religious, pseudo-left has for the French and Russian revolutions and other such failed revolutions.

No comments:

Post a Comment